Introduction

The previous article on the danger of videogames got some interesting replies, notably from Mark Saroufim, who made a video which I suggest everybody to watch.

First, let me recap my position.

Dopamine, Opportunity Cost and Addiction

I think videogames are dangerous for three main reasons:

-

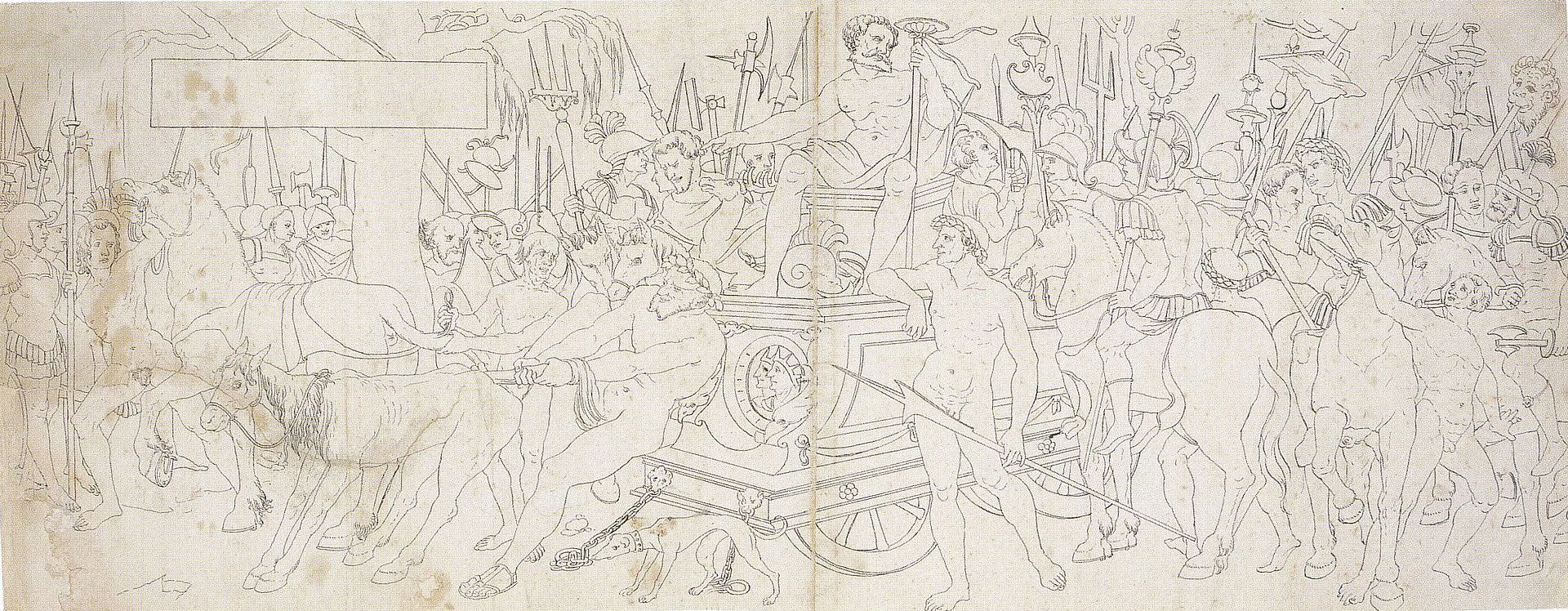

Desensitization to reality. You destroy your effort-reward system messing it up with artificial spike of dopamine. The same thing happens with browsing internet, watching porn: all of them are very modern activities from an evolutionary standpoint. See this image for a nice summary of the topic.

- Opportunity Cost. Life is hard. You can either wake up one day with an autoimmune disease, you can lose your cushy job or worse, you can have no direction for your future and follow the mainstream guidance. There are countless activities (while being less “fun” in the short term, though more gratifying in the long run) that can give you infinitely more return for the time you spend on them. Let’s draw from my personal experience:

- Reading Good Calories Bad Calories opened my mind to the fact that autoimmune disease could be diseases of civilization. No doctor has ever told me that.

- Reading Wall street Playboys taught me that enteprise software sales could be the place to learn entrepreneurial skills and where I could get paid the highest. Most of my colleagues got into slave consulting positions.

- Reading Hayek, Taleb and Popper I discovered that much of what we hear in the common discourse is BS. I feel free to choose my own goal and to determine my future, without taking seriously mainstream culture.

I spent 10 years of my life playing videogames but I cannot pinpoint similar epiphanies during the process. What I learnt in the games, stayed in the games. There was no transfer of knowledge.

In short, life is too complex to give yourself time to indulge in activities that addict you and don’t give you anything concrete in return.

- Addiction. Games are engineered to make you play “just another turn”. I remember playing League of Legends while trying to reach a competitive positioning in one of the top tier league (the “heaven” for those who got really sucked into the game). Some mechanism disgusted me such as the punishing re-spawn time, the boredom of the first 15 “farming” minutes or the clunkiness of certain characters. However, I felt I needed to raise my position in the league and I continued playing just to get the shiny badge that would signal my advanced status. How do you call this love-hate relationship with an object? Addiction.

We don’t always need evidence not to perform a certain action, especially when the domain is uncertain (In our case we did not “solve” for sure human psychology) and the downside is potentially huge. Call it Lindy, Precautionary Approach or refer to Hayek’s knowledge problem, I really don’t care.

In matter of obscure domain, I look at tradition: we weren’t exposed to this kind of artificial digital stimulus which could mess up our brain.

Objections

Can videogames teach something?

In the above mentioned video, Mark Saroufim makes a compelling case as to why games can teach. In his opinion, reading, memorizing and studying textbooks is not effective. You learn better by doing. Example: you might absorb very little while reading a book about game theory whereas in a competitive online game where you get hurt when you fail to understand how incentives (see for example League of Legends or DOTA) move people, you internalize better the concept.

In this sense, videogames are an alternative way of learning complex concept by trial and error. Mark insists that tinkering, experimenting and building is the best way to learn a subject (with an important point that “educational games” suck).

Even more, board games are worse than videogames since they have a higher barrier of entry (reading a lengthy manual, understanding the rules, long playing times,…) that hampers the tinkering process typical to games.

Some examples

Mark makes several examples of videogames that aligns with what he is thinking, here you will find the pointer to the video when he talks about them:

- Diplomacy: geopolitical strategy games that can teach you negotiation, how rulers might think and good allocation of resources.

- Crusader Kings II: strategy game that shows you how the power dynamics were working in the Middle Ages.

- Dota II: strategy games that can teach you cooperation, warfare and psychological mind games.

- Factorio: real time strategy/ survival game that can teach you fundamental concepts of programming and automation.

The anthithesis

To summarize Mark’s point, games are useful since they are an unique and fun way of teaching you complex concepts, that you would not experience using traditional methods.

While this point got me thinking, I believe this kind of reasoning only considers the “benefits” part of the equation while disregarding the “costs”. It is undeniable that videogames can teach you something and might also be an original way to introduce you to programming or history for example. However what is the cost?

Counterarguments

It is not a continuous learning process

What are the incentives of the creator of these games? What do they try to accomplish?

We should considers the most successful examples of this category and not the solitary Russian hermit indie creator (i.e. see for example Aurora 4x, always wonder if the creator had applied the same genius to business what he would have achieved). Looking at the structure of the incentives of the makers we can draw some interesting conclusions.

Digital games are designed to be continuously played since the creators make money not only on one-time purchases (i.e. Factorio) but also on subsequent “add-ons” (i.e. Crusader Kings II). Even then the goal is to make you stay on the game as long as possible, as simple as that. Videogames are a time-sucker (and the most well designed ones become addictive). This bring a first problem to Mark’s thesis.

There will be a point where you stop learning what the game has to teach you. Imagine that the games does give you 80% of the total benefit for the first 10 hrs of gameplay where you learn the mechanics and the remaning 20% is given out little by little in the hundreds hour that follow. The second part is the “time-sucker” one and should be avoided.

Where do you draw the line between the useful part (where you actually learn something and the benefits outweigh the costs) and the harmful one (where the designers try to hook you on the platform)?

In my personal experience, I always recognized the potential learning benefits as a justification to get the dopamine hits that you get while leveling up, getting that new item, winning a game against online competitors,…

The difference between a good and a bad game

While games can teach you something, how do you decide which game has something worth to tell you? If this difference is so blurred, do we really want to risk saying that all games can teach us something?

- Strategy games lover will tell you that their videogames taught them how to think

- Role-playing games lover will tell you that they help them hone their imagination

- Action-game lover will tell you that they help with their reflexes

Again by which criteria do we decide that a game is more “clever” than another?

Let’s draw a simplistic model of the main part that compose a videogame:

Videogame = Learning + Escapism + Addiction Mechanism (levels, competition,…)

We agree that the “fun” part lies in the latter two components and, while it is instrumental to the former, it needs to be contained so that the learning part gets the best share. A videogame which focuses only on guiding your character in an imaginary land for me would be little learning a lot of escapiscm. If it is based on online, then the third part would grow. On the contrary, a game like Factorio might be strong in the first and the third component, while a game like Crusader Kings II is complete, in a sense that, while it teaches you something, it definitely puts you in another world for the time spent playing.

The question remains: how do we decide which part outbalance the other? And if we cannot, do all the games have to teach us at least something or some are worse than the others?

The majority of my old videogamers friends are still in the loop playing League of Legends after 8 years. Evidently only superior minds can use games to spark an interest into a subject, control the monkey mind that would like to spend 5 hours in front of a screen and then investigate the topic with the real stuff. Even then, I would argue is still not the only choice to get interested in a subject.

Weak translation of skills to real life

The most important point: how do the skills that you learn in games translate in real life? Do we really agree on the notion that videogames are a “gym” where you exercise real life skills?

If that were the case:

- strategy game master (the same way chess players, here the digital element is not influential, see Taleb’s tweet below) would be masterminds, bilionaires and exceptional businessmen.

- rpg game master would be excellent fiction storytellers and writers

- geopolitical strategy game masters would be excellent negotiators

- survival game masters would be excellent hikers and survivalist

Friends, what's the real life performance of chess players? How do they fare in, say science and business?

— Nassim Nicholas Taleb (@nntaleb) September 16, 2018

Think about the majority of people who play. Is it really an enhancement tool for their life or they are simply escaping from something? Do they look strong and healthy as if they have done everything that needs to be done before playing?

Let’s take a person who invested 2k hours into Factorio. Is it really worth it? Could they have spent that amount of hours in something with far more return? Probably yes.

My opinion is that translating ability from one domain to another is a different type of skillset (and kudos to Mark for being able to do it, but the vast majority of people don’t have his mind), and you would be better off in focusing on the real thing from the start. If you want to learn coding, start doing it, maybe developing a small application. If you want to learn survival skills, go out in nature (you will find Mother Nature very different from Disney movies). If you want to learn negotiation, start selling a product.

Digression on learning skills

On a side note, do these game really teach you the correct real life skills? I doubt so.

I can report you my personal experience, after playing years of League of Legends and Europa Universalis in my group of friends, all of them got “average” job even though they have a way above average intelligence, they don’t apply as much as they could in their work and personal life and they don’t have this incredible strategic mind.

They are terribly average, anesthetized by this digital overstimulation.

I speculate that videogames are a way to cope with lack of objective, boredom and routine and make it bearable.

Comments